Can the Earthquake Lead to Peace in Nepal ?

-Adhik Badal

Though there is contention over the specific contribution of natural disaster to violentconflict, several climate change literature suggest that natural calamitieswill likelybe politically destabilizing during post-disaster settings. For example, typhoon Haiyen of 2013caused severe devastation in South East Asia. In itsinstant aftermath, eight people were crushed to death by a throng of looters at a government warehouse in the Philippines, and gunfire between armed men and security forces concluded with a mass burial.

However, some scholarship notes that disasters may also become a momentum for building peace. Disasterscan create new grounds for interaction between different political parties, such as the coordination of international relief or joint management disaster response, generating opportunities for cooperation and dialogue. Peace scholar, WilliamZartman outlined that disasters can create a moment that is ripe for negotiation, temporarily ceasingfurther violence, and presenting an opportunity for nonviolentsettlement of conflict.Disaster cancreate apolitical vacuum in affected areas, allowing space for political actors to work together and to foster apro-peace attitude among leadership.

The 2004 tsunami brought majordevastation in South East Asia, most severely affecting Aceh province of Indonesia and Sri Lanka. More than 200,000 deathswere reportedand millions were displaced across the region. When the tsunami struck, Sri Lanka and Aceh were bothexperiencing civil war. However, the tsunami impacted both of these countries in very different ways. Indonesia headed towards the path of peace, whileSri Lanka was stuck with large intensity of conflict. Under the guidance of the European Union, a peace agreement between Free Aceh Movement (GAM) and the Indonesian government was reached in 2005. In Sri Lanka,the peace process stalled once again creating mistrust between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the government. The Sri Lankan government brokethe ceasefire,launchedmilitary might,and eliminated the LTTE in 2009amid widespread allegations of grave human rights violations.

The case of Indonesia shows that disasters can produce a climate that is ripe for the benefit of peace. However, the case of Sri Lanka demonstrates the opposite.As emphasized by notable peace scholars,two factorsseem to matter the most. First, politicization of the disaster response can lead to an ineffective management of the disaster responseas well as opposition to a concurrent peace process. Second, the international community can play a pivotal role in peacebuilding process during post-disaster context.

In Sri Lanka, during the post tsunami period,political parties attempted to create a joint aid management mechanism, which failed, and the government institution of disaster management proved to be ineffective. Hundreds of NGOs started independent reconstruction activities, undermining the centrally administered response, blurring accountability. Conflict further escalated over unequal distribution of aid.

In Indonesia, the government created a separate agency, the Agency for the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Aceh, which distributed the humanitarian aid. Contrary to Sri Lanka, Indonesian disaster relief processes were administered without any overlap. The agency was apolitical, centrally administered, inclusive, and community owned. All projects were to be approved by a single national agency, leading to greater accountability than in Sri Lanka, where the majority of NGOs channeled their aid without any coordination and accountability.

The second lesson learned from Sri Lanka and Indonesia concerns proactive international facilitation, which is a key component in resolving intractable conflict during post-disaster settings. In Sri Lanka, Norway acted as a mediator butassumedapassive role during negotiations. Therefore, some scholars charged Norway for not seeking to bring parties to the realization of “Mutually Enticing Opportunities.” In Indonesia, MarttiAhtisaari, the Noble Peace Laureate, was a leading mediator, actively involved in the peace negotiations. Ahtisaari held severalformal and informal dialogues with the conflicting parties, and drafted the first version of the peace agreement during the post-Tsunami period.

Nepal is in a similar positionas these two countries a decade ago. However, Nepal’s current post-war political settings have a fewnuances. The 7.6 Richter scale earthquakeand its countless aftershocks have created catastrophic devastation in Nepal including 8,778 deaths, more than 22,000 injured, and half a million structural damages. The earthquake has added further challenges to complete the constitution writing process.

However, the earthquakehas also generated trust and cooperation between political parties and brought themtogether to work for strategic peacebuilding in the country. The 16-point recent political deal between major political parties for the constitution writing process can be taken as an exampleof the positive impact of this catastrophe, as it has generatedhope for the democratization process in Nepal. But the hidden power seeking interest of Nepalese political partiesto deal with post-disaster management along withthe post-war democratization processmight create mistrust in the future. Conflict theorists argue that cooperation between the parties is more likely during emergency phase and a reemergence and intensification of conflict is likely in the reconstruction phase that follows. Thus, it should be noted that power sharing is a pivotal part of the peace process. However, linkinghumanitarian activitieswith the political process might cause the democratization process to become a never-ending game in Nepal.

Lessons learned from Indonesia show that disaster management and peacebuilding are two different issues and each should be dealt with differently in order to seizethe opportunity provided by this tragedyto bring aboutpeace. The ordinance that was passed recently on formation of reconstruction authority under the Prime Minister’s leadership seems to be positive.However, the structure of the agency that hasproposed does not seem to be promising. The minimal presence of experts on the board, and the current bureaucratic procedures are the two reasons that are likely to jeopardize the effectiveness of this agency. In the past, the proposed bureaucratic system preferred by Nepalese politicians has proven ineffective. Locals and donors alike have viewed these systems as highly corrupt and untrustworthy. Therefore, the government of Nepal should discuss more with experts to make this agency more independent and apolitical while bringing a concreate plan and objectives. Only when,channeling aid through this agency will be more effective at rehabilitation and reconstruction activities. It will decrease level of corruption and restore trust among the donor community and the Nepalese people.

Similarly, the international community should encourage major parties to execute the recent political agreement, andcontinuedialogue with other parties that have not yet been included in the agreement process,while responding to the earthquake situation in Nepal. This will promote political stability and a hope for the future. As soon as parties promulgate the constitution, theycan form a new governmentunder an active leadership in which the issue of ownership will be addressed. At this time the new government can receive more support and help from the international donor community. This will add further credibility to the handling ofpost-disaster reconstruction as well as help complete the democratization processes in Nepal. Therefore, Nepalese political actors should learn lessons from the post Tsunami trajectories in Indonesia and Sri Lanka to make the best ofthis disaster and build a shared foundation for peace in Nepal.

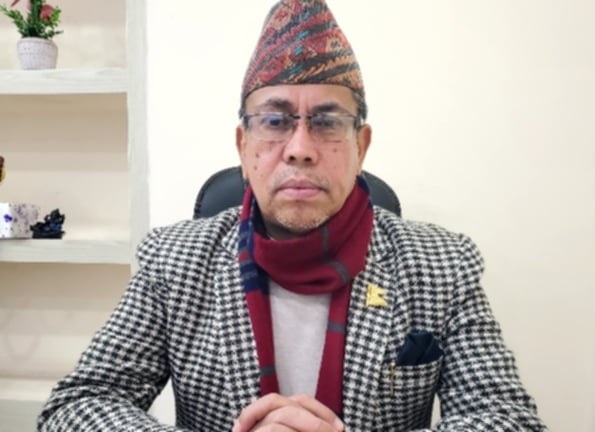

(The author holds master’s degree in International Peace Studies from the University of Notre Dame, USA. He is currently working at Namlo International a US based INGO with its head office in Colorado, USA.)